It’s almost surreal how the supply chain issues across so many industries have paralleled one another over the course of the past year. Of course, the unforeseen coronavirus pandemic is the one commonality that links all of the supply chain challenges. But the appliance, furniture, bedding and consumer electronics segments have all experienced compounding factors that have made product availability even more of a challenge than it already was.

The furniture industry has been hampered by ongoing lumber shortages. Bedding is still fighting through foam shortages caused by a late-winter deep freeze. And appliance makers have been hurt by social distancing measures that reduced their capacity to produce product.

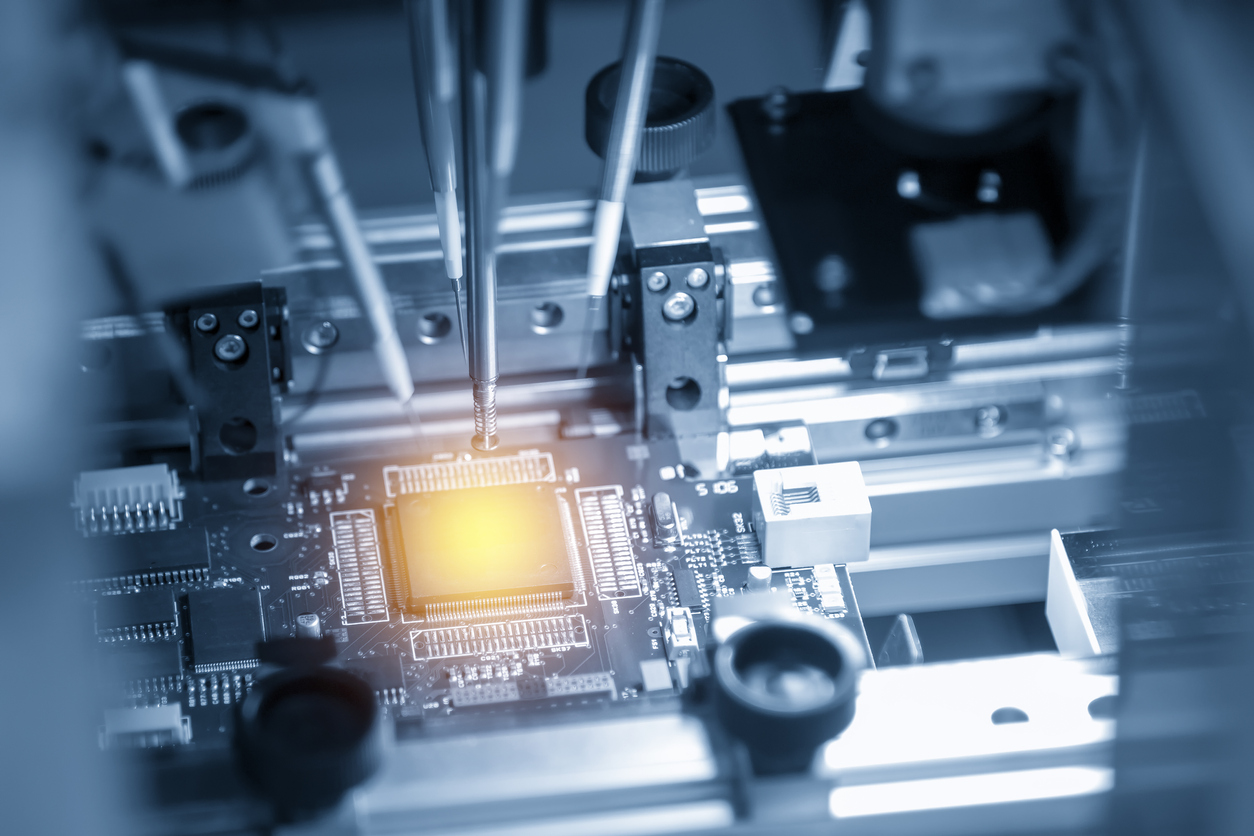

When it comes to consumer electronics, if you’ve been following the industry over the past year, you know that there’s been an ongoing component shortage that’s impacted nearly every piece of technology — as well as some of those smart appliances retailers have on their show floors. Everything from automobiles to TVs, computers, gaming consoles, smartphones, speakers, headphones, earbuds and so on have been impacted by the chipset shortage.

We know that consumer demand has been at an all-time high, which certainly doesn’t pair well with the manufacturing environment that brands have been operating through. Add to that factories having to shut down because of massive fires and the same Texas deep freeze that impacted the foam market. But that’s not all. We’ve recently come to learn that consumer tech brands themselves may have made things worse with early pandemic projections that were woefully wrong.

In a recent interview with BBC, Cisco CEO Chuck Robbins addressed the shortage and partly put the blame on manufacturers for a major miscalculation of demand as lockdowns were put in place last year.

“Semiconductors go in virtually everything, and what happened was when COVID hit, everyone thought the demand side was going to decline significantly and in fact we saw the opposite,” he said. “We saw the demand side increase. Which was a complete shock to so many of us.”

According to Robbins, manufacturers sent lower demand projections to component providers, who then reduced their orders. And all of that, of course, was further exacerbated by the massive rise in demand.

Help appears to be on the way, though — eventually.

Robbins told the BBC that he anticipates the industry will “get through the short term” in the next six months or so. But he sees the catchup process lasting another 12 to 18 months. To aid in that process, a number of chip manufacturers are working to build new production factories here in the United States as quickly as possible. And those efforts were further boosted by an executive order from President Biden in late February that focused on securing American supply chains with added emphasis on the chip market. Additionally, the president’s infrastructure plan calls for $50 billion in funding for chip manufacturing and research through the CHIPS Act.

The Semiconductor Industry Association noted that the global share of semiconductor manufacturing capacity in the United States has taken a dive over the last three decades, decreasing from 37% in 1990 to just 12% today. SIA points to substantial subsidies being offered by global competitors and flat levels of investment in semiconductor research.